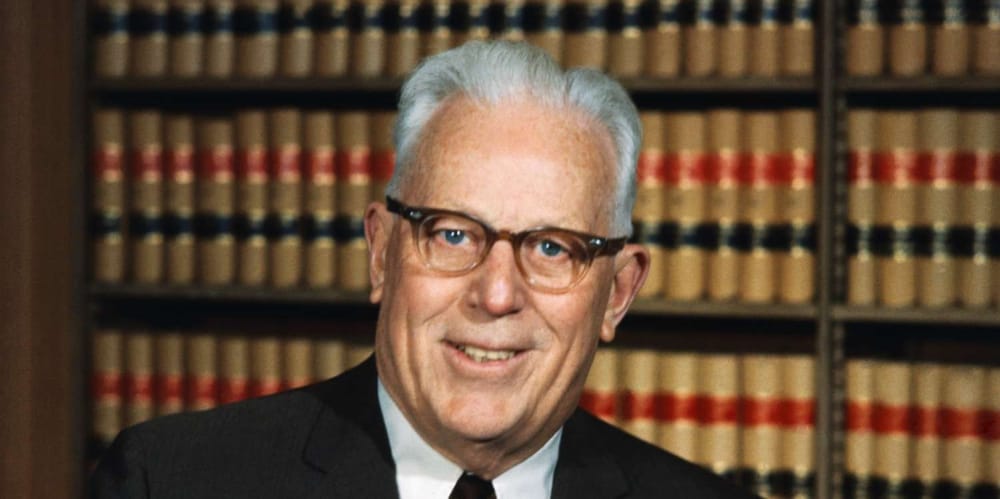

In the landscape of American legal history, few figures have wielded as transformative an influence on civil rights and liberties as Chief Justice Earl Warren. Appointed to the Supreme Court in 1953, Warren presided over a period of profound social transformation until his retirement in 1969. His tenure is marked by a series of landmark decisions that not only redefined the contours of American constitutional law but also catalyzed significant societal change. Under his leadership, the Warren Court became synonymous with judicial activism aimed at expanding individual rights and ensuring equality under the law.

Warren's legacy is characterized by a commitment to liberal principles, particularly in areas such as racial equality, voting rights, criminal justice reform, and the separation of church and state. This article explores several pivotal cases during his era that underscore his dedication to these causes. By examining these decisions, we gain insight into how Warren's jurisprudence continues to shape contemporary legal discourse and civil rights protections.

Brown v. Board Of Education (1954)

The significance of Brown v. Board Of Education (1954) extends beyond its immediate impact on public education; it served as a catalyst for the civil rights movement and laid the groundwork for subsequent rulings that dismantled institutionalized racial discrimination. It influenced later cases such as Loving v. Virginia (1966), which struck down laws banning interracial marriage, and Regents Of The University Of California v. Bakke (1977), which addressed affirmative action policies. The decision also prompted further legislative and judicial efforts to achieve racial equality, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Brown v. Board Of Education (1954) remains a cornerstone of constitutional law, symbolizing the judiciary's role in upholding justice and equality.

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision delivered by Chief Justice Earl Warren, held that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal," thereby overturning Plessy v. Ferguson (1895) in the context of public education. The Court's reasoning was grounded in the detrimental effects of segregation on African American children, noting that it generated a sense of inferiority that undermined their educational opportunities. The decision emphasized that education is a fundamental right essential to the performance of our most basic public responsibilities and that segregation deprived minority children of equal educational opportunities. This landmark ruling marked a significant shift in the Court's interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause, setting a precedent for future civil rights advancements.

Brown v. Board Of Education (1954) stands as a pivotal Supreme Court case that fundamentally transformed American constitutional law and civil rights. The case arose from several consolidated lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of racial segregation in public schools under the "separate but equal" doctrine established by Plessy v. Ferguson (1895). The plaintiffs, African American children denied admission to certain public schools based on laws permitting public education to be segregated by race, argued that such segregation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The legal issue at the heart of the case was whether state-sponsored segregation of public schools was inherently unequal and thus unconstitutional.

Gideon v. Wainwright (1962)

The significance of Gideon v. Wainwright (1962) cannot be overstated, as it fundamentally transformed American jurisprudence by incorporating the Sixth Amendment's right to counsel into state law through the Fourteenth Amendment. This case laid the groundwork for subsequent decisions that expanded defendants' rights, including Miranda v. Arizona (1965), which established Miranda rights, and Argersinger v. Hamlin (1971), which extended the right to counsel to misdemeanor cases where imprisonment could be imposed. The decision in Gideon underscored the importance of legal representation in ensuring due process and equal protection under the law, reinforcing the notion that justice should not be contingent upon one's economic status.

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, overturned Gideon's conviction, holding that the right to counsel is a fundamental right essential to a fair trial. The Court's reasoning was grounded in the principle that a fair trial cannot be realized if the accused lacks legal representation, particularly given the complexities of legal proceedings and the adversarial nature of the criminal justice system. Justice Hugo Black, writing for the Court, emphasized that the right to counsel is a safeguard of liberty and justice, and its denial would undermine the integrity of any judicial proceeding. This decision effectively overruled Betts v. Brady (1941), which had previously held that such a right was not obligatory upon states unless special circumstances existed.

The landmark case of Gideon v. Wainwright (1962) addressed the fundamental right to counsel as guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution. The case arose when Clarence Earl Gideon was charged with a felony in a Florida state court. Lacking the financial means to hire an attorney, Gideon requested that the court appoint one for him. His request was denied based on the state law at the time, which only provided for court-appointed counsel in capital cases. Gideon represented himself at trial and was subsequently convicted. He filed a handwritten petition to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear his case, thus raising the critical legal issue of whether the Sixth Amendment's right to counsel in criminal cases extends to defendants in state courts under the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause.

Miranda v. Arizona (1965)

The significance of Miranda v. Arizona (1965) in American jurisprudence cannot be overstated, as it established the "Miranda rights," a fundamental component of police procedure in the United States. This decision has had a profound impact on law enforcement practices and has been subject to various interpretations and applications in subsequent cases. For instance, Dickerson v. United States (1999) reaffirmed the constitutional basis of Miranda rights, while Berghuis v. Thompkins (2009) clarified the conditions under which a suspect's silence can be interpreted as a waiver of these rights. The Miranda ruling continues to be a cornerstone in discussions about the balance between effective law enforcement and the protection of individual liberties.

The Court's reasoning in Miranda v. Arizona (1965) was grounded in the necessity of ensuring that individuals are aware of their rights when subjected to the inherently coercive environment of police custody. Chief Justice Earl Warren, writing for the majority, emphasized that the Fifth Amendment privilege is fully applicable during a period of custodial interrogation. To protect this right, the Court mandated that law enforcement officials must inform suspects of their rights to remain silent and to have an attorney present during questioning. This decision built upon earlier rulings such as Escobedo v. Illinois (1963), which recognized the right to counsel during police interrogations, and Gideon v. Wainwright (1962), which affirmed the right to legal representation.

The landmark Supreme Court case Miranda v. Arizona (1965) addressed the critical issue of protecting a suspect's Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination during custodial interrogations. The case arose when Ernesto Miranda was arrested and confessed to crimes without being informed of his right to counsel or his right to remain silent. The legal question before the Court was whether the Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination extends to the police interrogation of a suspect in custody. The Court, in a 5-4 decision, held that the prosecution could not use statements stemming from custodial interrogation unless it demonstrated the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the privilege against self-incrimination.

Loving v. Virginia (1966)

The significance of Loving v. Virginia (1966) extends beyond its immediate impact on anti-miscegenation laws; it laid the groundwork for future jurisprudence concerning marriage equality and civil rights. The case has been cited in subsequent landmark decisions, including Obergefell v. Hodges (2014), which recognized same-sex marriage as a constitutional right. Additionally, Loving has been referenced in discussions about equal protection and substantive due process in cases like Lawrence v. Texas (2002) and United States v. Windsor (2012). By affirming that marriage is a fundamental right free from racial discrimination, Loving v. Virginia (1966) continues to influence legal discourse on equality and civil liberties.

The Court, in a unanimous decision delivered by Chief Justice Earl Warren, held that Virginia's law was unconstitutional. The Court's reasoning emphasized that the freedom to marry is a fundamental right inherent to the liberty of individuals, and denying this right on a racial basis violated the central meaning of the Equal Protection Clause. The Court further articulated that distinctions drawn according to race were subject to "the most rigid scrutiny" and that the state had failed to demonstrate a compelling interest to justify such racial classifications. This decision reinforced the principle that marriage is one of the "basic civil rights of man," as previously recognized in Skinner v. Oklahoma Ex Rel Williamson (1941), and underscored the importance of individual autonomy and equality.

The Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia (1966) is a landmark decision that invalidated laws prohibiting interracial marriage, marking a pivotal moment in the fight for civil rights and equal protection under the law. The case arose when Richard Loving, a white man, and Mildred Jeter, a black woman, were sentenced to a year in prison for marrying each other, as their union violated Virginia's anti-miscegenation statute, the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. The legal issue at the heart of the case was whether such state laws violated the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Reynolds v. Sims (1963)

The significance of Reynolds v. Sims (1963) lies in its affirmation of the "one person, one vote" doctrine, which has had a profound impact on American jurisprudence and electoral fairness. It reinforced the judiciary's commitment to protecting voting rights and ensuring equal representation, influencing subsequent cases such as Wesberry v. Sanders (1963), which applied similar principles to congressional districts, and Gray v. Sanders (1962), which articulated the concept of equal representation in elections. The decision also paved the way for future challenges to gerrymandering and malapportionment, shaping the landscape of electoral law and reinforcing democratic principles across the United States.

In its decision, the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, held that the Equal Protection Clause does indeed require that both houses of a state legislature be apportioned on a population basis. The Court's reasoning emphasized that an individual's right to vote is unconstitutionally impaired when its weight is in a substantial fashion diluted compared to votes in other districts. The Court rejected arguments that factors other than population could justify deviations in district sizes, underscoring the fundamental principle that each vote should carry as much weight as possible. This decision built upon the precedent set in Baker v. Carr (1961), which established the justiciability of apportionment issues, and further developed the Court's role in ensuring fair representation.

The Supreme Court case of Reynolds v. Sims (1963) addressed the critical issue of legislative apportionment and the principle of "one person, one vote." The case arose from a challenge to the apportionment of the Alabama state legislature, which was based on outdated population data that resulted in significant disparities in representation. The legal issue at the heart of the case was whether the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment required state legislative districts to be roughly equal in population. The plaintiffs argued that the existing apportionment scheme diluted their votes and violated their constitutional rights.

Baker v. Carr (1961)

The significance of Baker v. Carr (1961) lies in its establishment of the principle that federal courts can review and decide cases involving legislative apportionment, thus paving the way for subsequent decisions that further developed the "one person, one vote" doctrine. This case set a precedent for judicial intervention in ensuring fair representation, influencing later cases such as Reynolds v. Sims (1963) and Wesberry v. Sanders (1963), which reinforced the requirement for equal population districts in state legislatures and congressional districts, respectively. The decision in Baker v. Carr (1961) fundamentally altered the landscape of American electoral politics by affirming the judiciary's role in safeguarding democratic principles.

In a 6-2 decision, the Supreme Court held that the plaintiffs' claim was justiciable, meaning it was appropriate for judicial resolution. Justice Brennan, writing for the majority, articulated that the case did not present a non-justiciable political question because it involved constitutional rights under the Equal Protection Clause. The Court's reasoning emphasized that judicial intervention was necessary to ensure equal representation and protect citizens' voting rights. This decision marked a departure from previous rulings, such as Colegrove Et Al v. Green Et Al (1945), where the Court had refrained from intervening in apportionment issues, citing them as political questions.

The Supreme Court case of Baker v. Carr (1961) is a landmark decision that addressed the issue of legislative apportionment and the justiciability of political questions. The case arose when Charles W. Baker and other Tennessee residents challenged the state's legislative districting, arguing that the failure to reapportion districts since 1901 resulted in significant disparities in representation, violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The legal issue at hand was whether federal courts had the authority to adjudicate matters of state legislative apportionment, which had traditionally been considered a political question beyond judicial review.

Mapp v. Ohio (1960)

The significance of Mapp v. Ohio (1960) lies in its extension of the exclusionary rule to the states, thereby reinforcing the Fourth Amendment's protections nationwide. This case marked a pivotal moment in constitutional law, emphasizing the importance of procedural safeguards in criminal justice. It laid the groundwork for subsequent decisions that further defined and expanded individual rights, such as Miranda v. Arizona (1965) and Katz v. United States (1967). The decision also sparked ongoing debates about the balance between effective law enforcement and the protection of civil liberties, influencing numerous cases concerning search and seizure practices.

In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the exclusionary rule is applicable to state courts through the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. Justice Tom C. Clark, writing for the majority, emphasized that the right to privacy and protection from arbitrary governmental intrusions is fundamental and must be enforced uniformly across both federal and state jurisdictions. The Court reasoned that without such enforcement, constitutional rights would be rendered ineffective. This decision effectively overruled Wolf v. Colorado (1948), which had previously allowed states to decide whether to adopt the exclusionary rule.

The landmark Supreme Court case Mapp v. Ohio (1960) addressed the critical issue of whether evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unreasonable searches and seizures, could be admissible in state courts. The case arose when police officers forcibly entered Dollree Mapp's home without a proper search warrant, seeking a fugitive. During the search, they discovered obscene materials, leading to Mapp's conviction under Ohio law. The legal question centered on whether the exclusionary rule, which prohibits the use of illegally obtained evidence in federal courts as established in Weeks v. United States (1913), should also apply to state courts.

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969)

The decision in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School Dist (1968) has had a profound impact on subsequent jurisprudence concerning student speech. It established a foundational precedent for evaluating the balance between school authority and student rights, influencing later cases such as Bethel School Dist No 403 v. Fraser (1985), which addressed lewd speech at school assemblies, and Hazelwood School Dist v. Kuhlmeier (1987), which dealt with school-sponsored publications. Moreover, Morse v. Frederick (2006) further explored these boundaries in the context of speech promoting illegal drug use. Collectively, these cases illustrate the evolving nature of First Amendment protections within educational contexts, with Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School Dist (1968) serving as a pivotal touchstone for understanding and applying free speech principles in schools.

The Supreme Court, in a landmark decision, held that students do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate." The Court's reasoning emphasized that the armbands represented a form of symbolic speech that was "closely akin to 'pure speech'" and thus entitled to comprehensive protection under the First Amendment. The Court further articulated that for a school to justify suppressing such expression, it must demonstrate that the conduct would "materially and substantially interfere" with the operation of the school. This standard set a high bar for censorship within educational settings, underscoring the importance of protecting expressive freedoms even in environments traditionally subject to greater regulation.

The case of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School Dist (1968) stands as a seminal decision in the realm of First Amendment jurisprudence, particularly concerning the rights of students within public schools. The case arose when a group of students, including Mary Beth Tinker and her siblings, wore black armbands to their Des Moines school to protest the Vietnam War. The school district, having preemptively banned such armbands, suspended the students, prompting a legal challenge on the grounds that their First Amendment rights had been violated. The central legal issue was whether the prohibition against wearing armbands in public schools, as a form of symbolic protest, violated the students' freedom of speech protections under the First Amendment.

Griswold v. Connecticut (1964)

The significance of Griswold v. Connecticut (1964) lies in its establishment of a constitutional right to privacy, which has had profound implications for subsequent jurisprudence. This case laid the groundwork for later decisions such as Roe v. Wade (1972), which extended privacy rights to a woman's decision to have an abortion, and Lawrence v. Texas (2002), which struck down laws criminalizing homosexual conduct. Additionally, Eisenstadt v. Baird (1971) expanded the right recognized in Griswold to unmarried individuals, further solidifying the principle that personal decisions regarding intimate relationships are protected from unwarranted governmental intrusion. Through these cases, the doctrine of privacy has evolved into a fundamental aspect of American constitutional law.

The Court, in a 7-2 decision, held that the Connecticut statute violated the right to marital privacy. Justice William O. Douglas, writing for the majority, reasoned that while the Constitution does not explicitly mention "privacy," various guarantees within the Bill of Rights create "penumbras," or zones, that establish a right to privacy. Specifically, Douglas pointed to the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments as creating a new constitutional right to privacy in marital relations. This reasoning was pivotal in establishing a broader interpretation of privacy rights under the Constitution.

The Supreme Court case of Griswold v. Connecticut (1964) is a landmark decision that addressed the constitutionality of a Connecticut law prohibiting the use of contraceptives. The case arose when Estelle Griswold, the Executive Director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut, and Dr. C. Lee Buxton, a physician and professor at Yale Medical School, were convicted under this law for providing contraceptive advice to married couples. The legal issue at the heart of the case was whether the Constitution protected the right of marital privacy against state restrictions on a couple's ability to be counseled in the use of contraceptives.

Engel v. Vitale (1961)

The significance of Engel v. Vitale (1961) lies in its reinforcement of the strict separation between church and state, particularly within public education. It set a precedent for subsequent cases involving religious activities in public schools, such as Abington School Dist v. Schempp (1962), which struck down school-sponsored Bible readings, and Lee v. Weisman (1991), which prohibited clergy-led prayers at graduation ceremonies. The decision also influenced broader Establishment Clause jurisprudence, as seen in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1970), which established the Lemon test to evaluate government actions related to religion. Engel v. Vitale (1961) remains a cornerstone case in American constitutional law, illustrating the Court's commitment to maintaining a secular public sphere free from governmental religious endorsement.

In a landmark decision, the Supreme Court ruled 6-1 in favor of Engel, holding that the state-sponsored prayer was indeed unconstitutional. The Court's reasoning, articulated by Justice Hugo Black, emphasized that the Establishment Clause was intended to prevent government interference with religion and to avoid the divisive potential of religious involvement in public institutions. The Court rejected arguments that the prayer was non-denominational and voluntary, asserting that any government endorsement of religious activity in public schools inherently violates the constitutional separation of church and state. This decision underscored the principle that even indirect government involvement in religious activities could lead to an impermissible entanglement with religion.

The Supreme Court case of Engel v. Vitale (1961) addressed the constitutionality of state-sponsored prayer in public schools, a pivotal issue concerning the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The case arose when the New York State Board of Regents authorized a short, voluntary prayer for recitation at the start of each school day. A group of families, led by Steven Engel, challenged this practice, arguing that it violated the Establishment Clause, which prohibits the government from establishing an official religion or unduly favoring one religion over another. The legal issue at hand was whether the state's endorsement and facilitation of a prayer, even if non-denominational and voluntary, constituted an unconstitutional establishment of religion.

Earl Warren's tenure as Chief Justice marked an era where civil liberties were significantly expanded through landmark rulings that continue to resonate today. His liberal approach towards interpreting the Constitution reshaped American society by promoting racial equality, ensuring fair representation, and safeguarding individual freedoms against governmental overreach.

The legacy left behind by Earl Warren is still felt today with many of these decisions continuing to shape our understanding of civil rights and liberties. He remains a towering figure in American jurisprudence whose impact on the legal landscape cannot be overstated—truly embodying what it means to serve justice without fear or favor.

Stay Ahead with Etalia.ai

🌟 Discover More with a Subscription 🌟

If you've found this deep dive into Earl Warren: chief Justice known for his liberal decisions in landmark civil rights cases insightful, there's so much more to explore with Etalia.ai. Our platform is dedicated to bringing you meticulously researched content that broadens your understanding of crucial legal and political issues.

✨ Enhanced with AI

This article has been rewritten and enhanced using advanced AI technology to demonstrate improved comprehensiveness, accuracy, and analytical depth while maintaining our scholarly standards.

Originally published: 2/19/2024 | Enhanced: 9/5/2025 | Scheduled for republication: 10/3/2025